Our Missing Men of March

This month we will cover Michigan’s Vietnam MIA from March 1966 – March 1971. We also have wonderful news on the recovery of two of the MIA personnel profiled here in last December’s story “The Lost Men of World War II.”

This month we will cover Michigan’s Vietnam MIA from March 1966 – March 1971. We also have wonderful news on the recovery of two of the MIA personnel profiled here in last December’s story “The Lost Men of World War II.” First, the good news.

81 years after his disappearance, WWII U.S. Army Air Forces 2LT Francis E. Callahan, the 22-year-old navigator of the missing B-24 Liberator Little Joe (#42-521850), was returned to his family for burial at Arlington National Cemetery. Pictured is his niece, Kathleen Callahan-Kaminski, receiving his burial flag on February 24, 2025.

Kathleen Callahan-Kaminski receives her uncle’s flag, 2LT Francis E. Callahan

Also after a loss of 81 years, 22-year-old waist gunner, U.S. Army Air Forces SSG Yuen Hop, was returned to California after being shot down over Germany. Seen here is his 96-year-old sister, Margery Wong, being presented with his burial flag at Golden Gate National Cemetery, February 5, 2025.

Margery Wong finally greets her big brother again, SSG Yuen Hop

Never give up.

2LT Francis E. Callahan

SSG Harry Medford Beckwith, III

We lead with the almost unbelievable story of 22-year-old U.S. Army Sergeant Harry Medford Beckwith, III of Lansing, MI. SGT Beckwith served with Troop D, 3rd Squadron, 5th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Brigade, 5th Infantry Division; this was already his third tour of duty in Vietnam. He was determined to make a lifelong career in the Army just like his father, Sargeant Major Harry Medford Beckwith, Jr., who was likewise in Vietnam after having served in both WWII and the Korean War. SGT Beckwith had already been hospitalized a few times but talked his way back into active combat after beating two U.S. medical boards. For his latest exploits during April of 1970, he had been awarded the Silver Star for holding off enemy troops with a machine gun and providing safe evacuation for his men while severely wounded from a grenade attack on the tank he was commanding. SGM Beckwith was present at his son’s award ceremony and noted approvingly that “he was bullheaded, just like me.”

Tragedy had struck the Beckwith’s in 1962 when their two youngest children, ages 11 and 9, had both drowned in a surprise flash flood, so Harry, the eldest, was the only one left. He was resolute in his decision to do himself, and his parents, proud in the military.

Events took another fateful turn for the family on March 24, 1971. SGT Beckwith was a crewmember on an OH-58A Kiowa that was hit by enemy anti-aircraft fire that then crashed shortly after departing Ham Nhi, South Vietnam. An extraction helicopter team was quickly dispatched to the crash site to recover his body, which they did. Once they were aloft, that aircraft also came under enemy fire and had to take quick evasive action. While executing an escape maneuver, SGT Beckwith’s remains fell through the helicopter door to the ground. Attempts by search aircraft to locate it proved unsuccessful, and his DPAA status was assigned as unaccounted for, Non-recoverable.

SGT Harry Medford Beckwith, III is memorialized on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (Punchbowl). His name is also inscribed along with all his fallen comrades on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, DC.

There is a memorial cenotaph for SGT Beckwith located next to his two young siblings, his mother, and SGM Harry Medford Beckwith, Jr. in Section 1079 of Beverly National Cemetery in Beverly, New Jersey.

SSG Beckwith’s memorial cenotaph

CDR Donald Joseph Woloszyk

24-year-old Naval flier from Attack Squadron 55, CDR Donald Joseph Woloszyk of Alpena, MI was solo piloting an A-4E Skyhawk (bureau number 152057, call sign "Garfish 401") on March 1, 1966. He launched from the USS Ranger (CV 61) as the second of four aircraft embarking on an armed recon mission over North Vietnam. CDR Woloszyk radioed that he was going to follow one of the other aircraft as he had lost sight of the leader in heavy clouds; he was not heard from again. After extensive searches, neither he nor a crash site were located. CDR Woloszyk’s DPAA status remains unaccounted for, Active Pursuit.

He is memorialized on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, and his name inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, DC. CDR Woloszyk also has a memorial cenotaph at Holy Cross Cemetery in Alpena close to his parents’ graves.

Four members of U.S. Army 128th Assault Helecopter Company,11th Aviation Battalion, 12th Aviation Group, 1st Aviation Brigade set out on a troop insertion mission in Cambodia. On March 17, 1971, their UH-1 Iroquois (tail number 16664) was shot down by heavy enemy ground fire. Aboard were crew chief SSG Craig Mitchell Dix, 21, of Livonia, MI; pilot CW3 Richard Lee Bauman, 22, of OH; co-pilot CW2 James Hardy Hestand, 21, of OK; and gunner SSG Bobby Glenn Harris, 19, of TX. SSG Harris was blown out of the door of the Huey when it was hit with gunfire before it impacted the ground. The bodies of the remaining crewmen were not found during search attempts at the time, and they were listed as unaccounted for.

SSG Craig Mitchell Dix

Only four of the five are memorialized on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, and their names inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, DC.

Not appearing on the monuments is CW2 James Hestand, who somehow managed to survive the crash but was taken prisoner almost immediately. He was freed February 12, 1973, in a group of 28 American POWs (18 servicemen and eight civilians) released by the Viet Cong at Loc Ninh, South Vietnam, about 10 miles south of Cambodia.

Former POW CW2 James Hardy Hestand being queried by American military at the prisoner exchange at Loc Ninh, 2/12/1973 (Photo: SSGT Herman Kokojan / USAF)

CW2 James Hestand speaking with military escort officers and other released POWs in the Travis AFB passenger lounge during the long flight home, 2/12/1973 (Photo: SSGT Phillip M. Porter / USAF)

On December 2, 2002, DPAA announced that SSG Bobby Harris’ remains were located by a joint U.S. / Cambodian investigative team. He was finally returned to the U.S. and buried at Fort Gibson National Cemetery in Muskogee County, OK, on September 3, 2004. Besides family members and the huge throng of well-wishers present to honor SSG Harris was CW2 Hestand, who spoke of SSG Harris’ final gallant moments of battle.

Based on all information available, DPAA assessed missing team members’ SSG Dix and CW3 Bauman’s cases to be in the analytical category of Active Pursuit.

CW3 Richard Lee Bauman

On March 25, 1969, three team members of the U.S. Army 4th Infantry Division were conducting a road interdiction in Kontum Province, South Vietnam. Their unit became involved in a firefight with enemy forces, and one member, SFC Prentice Wayne Hicks, 22, from AL, was seriously injured. Two team members, 20-year-old SFC Richard Dean Roberts of Lansing, MI and 19-year-old SFC Frederick Daniel Herrera of NM, loaded SFC Hicks onto a litter (military stretcher) and proceeded down a hill. At some point while being fired upon again, the three became separated from the rest of their unit and disappeared. A search April 5 by a recon team found some personal possessions, but no other signs of the three men; they were designated as unaccounted for.

According to Lansing State Journal reports, SFC Roberts had finished basic and advanced infantry training at Fort Polk (now Fort Johnson) the beginning of January, and by March 19 was assigned to the 4th Infantry near Pleiku, Vietnam; he went missing six days later. He left behind his parents; wife, Linda; and 2-year-old daughter, Melinda.

SFC Richard Dean Roberts

The three riflemen are memorialized on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, and their names inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, DC. SFC Herrera also has a memorial cenotaph at Santa Fe National Cemetery next to his parents’ headstones. SFC Roberts’ double-sided cenotaph is at Mount Rest Cemetery in St. Johns, MI next to his daughter.

DPAA assessed their case status to be in the analytical category of Active Pursuit.

SFC Richard Dean Roberts’ cenotaph next to his sister’s headstone (Photo: Russ Rademacher, Mount Rest Cemetery)

Two aircraft embarked on an emergency medical evacuation mission from Hue-Phu Bai to Da Nang, South Vietnam, on March 26, 1968. A crew of four plus three patients were flying as wingman in poor visibility conditions. Their pilot put the UH-34D Choctaw (bureau #144654, call sign “Murray Medevac Chase”) on instruments so that he could better try to see the lead aircraft. While under instrument control the copter went into a sudden nose-dive into the South China Sea. Search and rescue immediately got to the crash site and were able to rescue the pilot and co-pilot. However, the crew chief, CPL Larry Edward Green, 21, of Mt. Morris, MI and aerial gunner, LCPL Ernest Claney Kerr, Jr., 21, of OH perished as did the three patients they were transporting: LTCOL Frankie Eugene Allgood, 37, of KS; CPL Glenn William Mowrey, 21, of OH; and LCPL Richard Evancho, 20, of PA. None of their bodies were recovered and their status assigned as unaccounted for.

CPL Larry Edward Green

The names of the five are memorialized on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific and are inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, DC. In addition, LCPL Evancho (St. Mary’s Byzantine Catholic Cemetery); CPL Mowrey (Overly Chapel Cemetery); and LCPL Kerr, Jr. (Hillside Memorial Park) have memorial cenotaphs at their family cemeteries.

Based on all information available, DPAA assessed their cases to be in the analytical category of Active Pursuit.

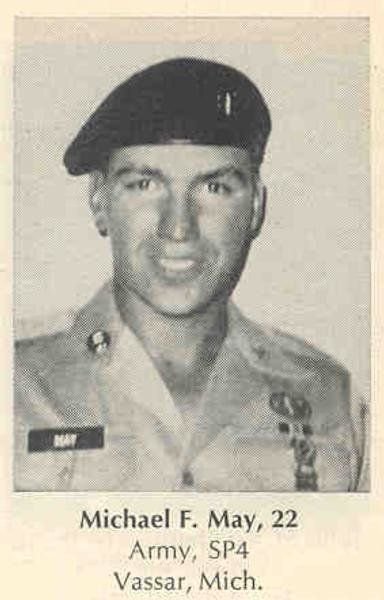

SP5 Michael Frederic May

On March 2, 1969, Vassar, MI native, U.S. Army SP5 Michael Frederic May, age 24, of SOA-C5 5th SFG, and ten other members of a Special Ops recon team embarked for a combat mission in Cambodia. As they approached their objective, enemy fire wounded one soldier in an ambush and the team retreated to elevated ground. Their call for a friendly gunship provided a temporary reprieve, but the enemy attacked again once it had departed. A rocket shot at the team exploded just over their heads wounding eight and killing two, SP5 May and team leader, SGT William Anthony Evans, 20, of WI. The wounded team members were able to escape, but they could not retrieve the two bodies as they were again overrun by the enemy. The two were subsequently listed as unaccounted for.

Both men are memorialized on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. Their names are also inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, DC.

Based on all information available, DPAA assessed their cases to be in the analytical category of Active Pursuit.

SGT Evans was the eldest of eight children. His father, a WWII Army veteran, was described as inconsolable after his son was lost and reportedly commit suicide a year later at age 42.

SP5 May’s family disclosed that he was a very gifted athlete in an array of sports, setting state records in high school and college. His military basic training was at Fort Knox (KY) followed by his Green Beret training at Fort Bragg (NC). He was posthumously honored by the Special Forces Association of Michigan by having a chapter named after him, The Michael May Memorial Chapter (SFA Chapter LV).

OH, LIFE OF MY LIFE

Oh, where lie your bones, oh, flesh of my flesh,

Oh, first-born pride of a mother's travail?

Do they lie exposed in green jungle mesh

Where greedy growth hides all hint of a trail?

Oh, where lie your bones, oh, blood of my blood,

Oh, sweet-bitter promise born of my womb;

Relentlessly washed by tropical flood;

Sun-bleached, abandoned without any tomb?

No clue found to mark where you bled

Nor a survivor that carnage to tell.

No body to mourn, no stone for your head,

No remains shipped from Cambodian hell.

Posthumous medals awarded your strife.

Oh, sad recompense, oh, life of my life.

Memorial poem written by Doris Kennard for her lost son, SP5 Michael Frederic May

Credits: Marty Eddy, Michigan Coordinator, National League of POW/MIA Families; DPAA; Lansing State Journal (4/10/1969); Baltimore Sun (8/20/1971; Flint Journal (8/25/1971); USAF; family photos

The story behind National Vietnam War Veterans Day

March 29th is celebrated as National Vietnam War Veterans Day, and you may be wondering why that specific date was chosen. The answer is simple and appropriate for the question: on that day in 1973, the last combat troops were withdrawn from Vietnam and the last prisoners of war held in North Vietnam arrived on American soil.

March 29th is celebrated as National Vietnam War Veterans Day, and you may be wondering why that specific date was chosen. The answer is simple and appropriate for the question: on that day in 1973, the last combat troops were withdrawn from Vietnam and the last prisoners of war held in North Vietnam arrived on American soil. Appropriately, on February 26, 1974, President Nixon proclaimed that March 29th would be the first Vietnam Veterans Day.

The current iteration of the day came about with the Vietnam War Veterans Recognition Act, signed into law in 2017, which formally designates March 29 of each year as National Vietnam War Veterans Day. That may sound like a semantical difference, but what sets them apart is that Nixon made a proclamation in 1974, whereas the 2017 edition was signed into law and recognized as a national day of observance.

With the celebratory day coming later this month, we are proud to host our second annual Vietnam War Veterans Day Luncheon on the same day, March 29th. The luncheon will celebrate the honor and service of our military members that fought in the Vietnam War, while providing them with a free meal prepared by our Executive Chef and his culinary team.

We would also like to take this opportunity to look back at The War Memorial, and the Alger family’s roles in the conflict. If the following looks familiar to you, that is because some of it is pulled from past historical writings done by our in-house historian, Betsy Alexander.

First, we will look at the Alger family service during the war:

The Vietnam War came calling for PFC Frederick “Fred” Moulton Alger, III (12/20/1934 – current) who entered the Marine Corps July 3,1959 just after getting his MBA. He was sent to Camp Pendleton, CA, and joined Company A, 3dAmTracBn (Rein), 1st Mar. Div. (Rein), FMF, CP, CA.

PFC Fred Moulton Alger, III and his company in 1959 (Camp Pendleton, CA)

If you know anything about the 1st Division, you know they are the oldest and most decorated Marine Division. They also pride themselves on being extremely big and extremely fierce. Fred was involved with “the operation, employment, maneuver, and maintenance” of amphibious assault vehicles in the 3D Amphibian Tractor Battalion, known since the mid-1970s as the 3D Assault Amphibian Battalion. PFC Alger stated that he and his mates were gung ho to get to Vietnam to do some serious damage – he used a bit more 1st Marines-type parlance – and were very disappointed they didn’t get called up. He also advised he became a crack shot with a rifle while at camp as a youngster, which he illustrated while in the service winning medals in Shooting. PFC Alger mustered out July 23, 1964, in New York City where he turned loose that 1st Marine motto of “No better friend, no worse enemy” successfully for decades on Wall Street.

Post-war peacetime meant that it was time to begin honoring the brave members of our US Armed Forces. The War Memorial began the process of putting together a plaque to commemorate the service of local Grosse Pointers.

The original criteria for inclusion in the plaque was written as, “The veteran must have lived in Grosse Pointe when they enlisted or were drafted; they must have served between the years 1963 and 1975; and they must have been physically present in Southeast Asia, which includes Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and on Navy ships serving in the area.”

One oddity that was found was that twice the Grosse Pointe News reported some sort of wooden plaque that was dedicated and installed on Memorial Day of 1974, but The Vietnam War wasn’t over until April 30, 1975, nearly a year later. This could possibly have been done to coincide with President Nixon’s proclamation earlier that year.

Another plaque, or an appended wooden plaque, with 340 names, was dedicated Memorial Day of 1984. It was photographed in the front circle of The War Memorial, but no written mention was made of installing that plaque; it may or may not have been. The final Vietnam War plaque that is present today, was bronzed, re-dedicated, and installed in the Alger House entrance hall Memorial Day of 1989.

To see all that The War Memorial is doing to commemorate the Vietnam War, click here.

February Michigan POW / MIA’s of Vietnam

The short month of February cost seven of our Michigan service personnel their lives during the Vietnam War; all of them were lost while flying. Today we are looking at and for those who are still Missing in Action from our state.

The short month of February cost seven of our Michigan service personnel their lives during the Vietnam War; all of them were lost while flying. As The War Memorial commemorates the Vietnam War in 2025, today we are looking at and for those who are still Missing in Action from our state.

On February 18, 1969, a KA-3B Skywarrior (bureau number 138943, call sign "Tenpin 017") with a crew of three U.S. Navy personnel took off from the aircraft carrier USS Coral Sea on a tanker mission over the Gulf of Tonkin (North Vietnam). Onboard were navigator AMS1 Stanley Milton Jerome, 31, of Detroit; pilot LCDR Rodney Max Chapman, 33, of Alpena; and CA crew member/navigator, AO1 Eddie Ray Schimmels, 29. The three were from Heavy Attack Squadron 10 (VAH-10), Carrier Air Wing 15 (CVW-15), USS Coral Sea (CVA-43), Task Force 77 (TF-77), 7th Fleet. While communicating on its return approach to the carrier, the Skywarrior disappeared suddenly from radar and crashed into the Gulf in the vicinity of (GC) 48Q YE 434 856. An extensive search of the area found no sign of the aircraft or its crew both immediately after the crash or the following day; the “Tenpin 017” men remain Unaccounted For.

LCDR Rodney M. Chapman of Alpena

Chapman had been a flier for eleven years and in the Navy for thirteen. He left behind his wife, Dorothy and daughter, Audrey at their base home in Oak Harbor, WA; AMS1 Jerome and AO1 Schimmels were single. All three are memorialized on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (“Punchbowl”), and their names are inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, DC. AO1 Schimmels also has a memorial cenotaph at Oakwood Memorial Cemetery in Oakwood, OK next to where his parents lie.

Based on all information available the three crewmen were categorized by the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) as Non-recoverable.

AMS1 Jerome, LCDR Chapman (both back row, left), and AO1 Shimmels (front left) with two unidentified men

***

On February 5, 1971, an AH-1G Cobra helicopter (tail number 66-15340) with two U.S. Army members took part in an extraction mission near Khe Sanh, Quang Tri Province, South Vietnam. The Cobra’s pilot, 19-year-old WO Carl Mitchell Wood of CO and his co-pilot, WO1 James Lee Paul, 22, of Koester Street in Riverview, MI, were members of Troop D, 3rd Squadron, 5th Cavalry Regiment, 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized). Shortly after takeoff, the Cobra entered heavy cloud cover and, while climbing for better visibility, impacted a mountainside and exploded. Aircraft accompanying the Cobra immediately began a visual search of the area and located the crash site at the base of Hill 1015. Investigation of the crash site recovered the remains of the pilot, CO Wood; he was buried at Fort Logan National Cemetery in Denver, CO. However, WO Paul’s remains could not be found and he was marked as Unaccounted For.

WO1 Paul is memorialized on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. His name is inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, DC. and his memorial cenotaph is in Arlington National Cemetery.

WO1 James L. Paul’s cenotaph in Arlington

Based on all information available, DPAA assessed WO1 James Lee Paul to be in the analytical category of Non-recoverable.

***

Last September, a group that should have received special government recognition decades ago finally did when the Congressional Gold Medal Act, S.2825 (118th) was signed by President Joe Biden. These were the Vietnam War U.S. Army personnel responsible for the emergency aeromedical casualty evacuation from the combat zone. Officially they were called CASEVAC, but they were more commonly known as Dustoff crews. Units were identified by their air ambulance call signs “Dust Off” then their assigned number.

The typical four-member Dustoff crews that manned these emergency evacuation flights frequently skewed very young, in their teens or early 20s. They knew they would be heavily fired upon while landing or rappelling down from their helicopters – usually “Hueys” - to get to the wounded, then again while boarding them for evacuation to camp hospitals. They had to be absolutely fearless as they faced a 1-in-3 chance each mission of themselves being killed.

On February 12, 1968, a Bell UH-1H Iroquois (tail number 66-17027, call sign “Dust Off 90”) took off from Ban Me Thuot, South Vietnam on a nighttime emergency evacuation mission to Gia Nghia Special Forces Camp. Aboard were the lanky 20-year-old crew chief, U.S. Army SFC Wade Lawrence Groth from Greenville, MI; SSG Harry Willis Brown, 24, medic, SC; CW3 Alan Wendell Gunn, 19, pilot, TX; and aircraft commander CPT Jerry Lee Roe, 25, TX.

SFC Wade W. Groth of Greenville

They were all members of the 50th Medical Detachment, 43rd Medical Group, 44th Medical Brigade. The aircraft failed to reach its destination, and an extensive search was initiated, but search and rescue teams were unable to locate the Huey. The entire “Dustoff 90” crew remain Unaccounted For.

SFC Wade Lawrence Groth and the other three men are memorialized on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific and on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, DC. His memorial cenotaph is at the Groth family plot at River Ridge Cemetery in Belding, MI.

Based on all information available, DPAA assessed all four missing crew members of the “Dust Off 90” to be in the analytical category of Active Pursuit.

U.S. Army Dustoff Memorial, Fort Sam Huston, TX

***

U.S. Navy LT Robert Clarence Marvin, 27, from Dexter, MI, served with Attack Squadron 115 aboard the USS Hancock (CVA 19). On February 14, 1967, LT Marvin piloted a single-seat A1-H Skyraider aircraft (bureau number 139805, call sign "Arab 511") that launched from the Hancock on a combat mission over North Vietnam. Ten minutes later, he radioed that he was rapidly losing oil pressure and would return to the ship. Shortly he radioed again that he would have to immediately ditch the aircraft in the Gulf of Tonkin. This was the last communication from LT Marvin; he was not seen or heard from again. His wife, Mary, was notified of his loss at their on-base home on Crusader Avenue at Lemoore NAS. 58 years later he remains Unaccounted For.

Lieutenant Marvin is memorialized on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific and his name is inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, DC. His cenotaph is at Rock Island National Cemetery, Rock Island, IL.

LT Robert C Marvin’s cenotaph

Based on all information available, DPAA assessed LT Marvin’s case to be in the category of Non-recoverable.

***

U.S. Army Specialist 4 Arthur Wright, 31, of Lansing served in Battery A, 1st Battalion, 44th Artillery Group. On February 21, 1967, he was manning a listening post at the gate of a U.S. Marine Corps combat base in Quang Tri Province, South Vietnam, with two other soldiers. During his shift, SP4 Wright told his two companions that he was going out to check the perimeter wire for intrusions, and that if he did not return by a certain point to report him to the Battery A orderly room (administrative office). He then left his post and proceeded forward, where he told a crew from Battery B that he was going to check the wire and not to shoot. SP4 Wright headed for the wire and was not seen again. Subsequent searches for him or his remains were unsuccessful.

Specialist 4 Wright is memorialized on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific and his name inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, DC. Based on all information available, DPAA assessed the case to be in the analytical category of Deferred. Per the DPAA, Deferred means that “there are no new or viable leads, or have restrictions to site access which makes field operations impractical.”

SP4 Wright left behind his wife, Uvah, and four children. Uvah passed away in 2016 at age 84, never remarrying. His memorial cenotaph is at Chapel Hill Memorial Gardens in DeWitt, MI adjoining Uvah’s headstone.

SP4 Arthur Wright’s cenotaph with wife in DeWitt

35-year-old pilot, U.S. Army Chief Warrant Officer 2 Marvin Maurice Leonard from Grand Rapids, was a very well-seasoned member of Company C,159th Aviation Battalion, 101st Airborne Division. He was a 16-year Army veteran, and a Distinguished Flying Cross and Air Medal recipient; this was his second tour of duty in Southeast Asia. He had served in Korea in 1966 for one year before transferring to Germany for another year. He was in Vietnam for 10 months starting in late 1968, then back to Germany for a year. He returned to Vietnam in November of 1970, where he was making flights into Laos.

CW2 Marvin M. Leonard of Grand Rapids

On February 15, 1971, he was flying "Regard 25," a CH-47C Chinook (tail number 18506) carrying four other crew members of Company C plus one passenger, taking part in a combat support resupply (fuel carrying) mission over Laos. During the flight, "Regard 25" caught fire, exploded, and crashed near the Pon River in Savannakhet Province, Laos. Another helicopter that had witnessed the incident performed an aerial search of the crash site but found no sign of the crew. The remains of the crew chief, SP4 Donald Everett Crone, 22, CA; door gunner, SP4 Willis Calvin Crear, 21, AL; flight engineer, SP4 John Lynn Powers, 22, ID; and passenger, WO Barry Frank Fivelson, 21, IL were eventually recovered and identified December 11, 2000. However, the remains of 25-year-old 2LT James Harry Taylor, CA, the aircraft commander, and CW2 Leonard were not. Based on all information available, DPAA assessed their cases to be in the analytical category of Active Pursuit.

Official badge of the “Regard 25”

Today, CW2 Leonard and 2LT Taylor are memorialized on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific and their names also inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, DC along with the other crew members. Rosettes were placed on the two monuments next to their four companions’ names once their DPAA status changed to Accounted For. A separate monument to the downed crew of the “Regard 25” is located at Arlington National Cemetery in Section 6, Site 8016.

Memorial to the “Regard 25” crew at Arlington

CW2 Leonard left behind a wife, Doris and three young children, two daughters and a son. A church memorial service was held for the benefit of his family and friends in Grand Rapids, April 16, 1971.

In his last letter to his family Leonard wrote, “I feel I’m in Vietnam so our children, and others, can play in the schoolyard in peace and see Old Glory fly. Also, you can bet on our POW’s getting some relief soon. I won’t even rule out a couple more attempts to rescue them, like the last one. Pray for Peace.”

Vietnam Helicopter Pilot and Crewmember Monument, Arlington National Cemetery

CREDITS: Thank you to Marty Eddy, Michigan Coordinator, National League of POW / MIA Families; and DPAA, Fort Sam Huston, and Arlington National Cemetery for information and photos.

A Bit of Good Old English Cooking

There are a few names that can be mentioned to longtime War Memorial visitors that evoke strong sentiment, such as Miss Mary Ellen Cooper, Vincent DePetris, and Chet Sampson. But one name recalled with great affection really stands out as she kept the nascent Association organized, rolling smoothly, and well fed – its first employee, Mrs. McGinty.

There are a few names that can be mentioned to longtime War Memorial visitors that evoke strong sentiment, such as Miss Mary Ellen Cooper, Vincent DePetris, and Chet Sampson. But one name recalled with great affection really stands out as she kept the nascent Association organized, rolling smoothly, and well fed – its first employee, Mrs. McGinty.

The story began in England in 1918, when 25-year-old Irishman, Francis (“Frank”) J. McGinty from County Down, found himself happily separated from both the British Army and WWI after being shot once in the leg and gassed even more times. He landed in Liverpool, England and happened upon a lovely blonde lass with a big, ready smile and dimples, Miss Anne Franklin. The 21-year-old Liverpudlian had been working for the Lyons’ restaurant and hotel chain in Britian and Wales as a waitress and then as a hostess. She found she excelled at cooking, serving, and hospitality, and loved the work. Not long thereafter, the couple married and settled down in Liverpool and soon had two daughters, Norah and Anne.

After a few years they decided to “move across the pond” to America. Francis went first in 1923, to test the job market; Anne and the girls would follow once he was established. By 1926, he was ready. Francis was situated in Detroit, working at the Detroit Steel Products Company, which was located where the huge GM Factory ZERO now sits near Hamtramck. He toiled away with 1,500 Americans producing the in-demand Detroit Springs used in the majority of automobiles and the wildly popular Fenestra steel windows. All Anne had to do was wait in Windsor, Ontario while she was being processed, then join him across the River in Detroit. She quickly found a job as hostess at the upscale Prince Edward Hotel on Ouellette and Park Streets. Once allowed in as a U.S. citizen, she had successive hospitality jobs at affluent downtown Detroit locations: the beautiful Colony Club on Park; the Women’s City Club; and as assistant manager of the Savoyard Club atop the Buhl Building. She also worked on the hallowed 14th Floor of the General Motors Building in their exclusive Executive Dining Room. These were jobs that were not for the faint of heart and served her well, getting her “maximum face time” and experience with the upper echelon of greater Detroit business and society.

Briefly she took on a partnership in a somewhat unusual business venture: a small cottage rental business in the Upper Peninsula’s rather desolate village of Newberry. The census count for Newberry in 2020 was still under 1,500 citizens, and it remains billed as “the Moose Capital of Michigan” to this day. Up there, decades ago, Anne was reportedly “very lonesome” and possibly bored with no people, five cabins, and many moose; she quickly abandoned the Newberry partnership for Detroit again.

To enhance her education of the hospitality business, Anne attended Wayne University (now Wayne State University) and completed their Institutional Management, Nutrition, and Quality Cooking and Buying courses. She also studied at Scranton’s Women’s Institute of Arts and Domestic Sciences. Her next job was not as an assistant or hostess, but as the manager of Detroit’s old Chimes Cafeteria for three years. She now expertly knew the daily ins-and-outs of running an institutional food business, back and front of house.

In spring of 1949, shortly after its inception, the Grosse Pointe War Memorial Association appointed her their House Manager, with Francis joining her as the Houseman (maintenance). Anne was the cook, housekeeper, Daily Events poster, and general organizer of everything House-related. Francis was all manner of heavy cleaning, repair, upkeep, and overnight security guard. If it was on the property, he deep cleaned and painted it - repeatedly.

The McGinty’s, undated

The McGinty’s lived on the second floor inhabiting the northern wing, the former servants’ quarters. The original horseshoe-shaped cluster of seven very small rooms, bathroom, and back stairs were turned into an apartment featuring a living room, dining room, kitchen, two bedrooms, and bathroom, with their own private stairs. At night they would stroll through the gardens or sit by the lake and enjoy the view, probably in the manner the Alger’s used to do so before them. Their two daughters were now grown and married, and there were curious grandchildren who were known to prowl the rooms and grounds afterhours and on holidays.

Three generations of McGinty’s,1955

The former Alger House had nothing in it when taken over by the War Memorial Association, so the grandiose idea of soon holding numerous large events and preparing and serving food was daunting, even to someone with such an extensive food service background as Anne McGinty. The very first items purchased were fifty card tables and 200 folding chairs as they needed something for the Board, Committee Members, early guests, and the McGinty’s to sit on and work from.

The just-created Board of Directors encouraged “friends” of the new “Memorial Center”, as it was long commonly referred to, to visit “flea markets and church sales” to scavenge for cheap but necessary kitchen implements, food preparation, and serveware. The idea of scoring an inexpensive mixer, 50-cup coffee urn, or a used vacuum cleaner was a very big deal back then to them. The great Robert Tannahill brought in the House’s large furnishings (and antiques) via donations – at which he and his Rolodex famously excelled - and he sometimes dug into his own personal collection. But the actual goods needed to operate the business and prepare and serve food were left to the others to secure, and Mrs. McGinty had long but realistic lists of items required to get the Memorial Center up and running like a top.

Success was immediate and great. She cooked for and served a variety of groups from the beginning, such as the Rotary, Optimists, Soroptimists, Kiwanis, Men’s Garden Club, and Veterans Club, and the men’s clubs demanded meat meals. There were even more youth and women’s clubs to plan meals for, plus plenty of teas, special events, outside groups, and frequent dances that kept her hopping.

The Board were very effusive in their respect for the McGinty’s valuable work, particularly Anne’s, and proclaimed that “as of July 1,1950, the McGinty’s should get an additional $25 per month.” For the first fiscal year ending July 31, 1950, Mrs. McGinty earned $3,300 ($275) and Mr. McGinty $3,000 ($250) with a $100 (split) Christmas bonus. The Board of Directors also gifted them a clock.

Beside always earning slightly more than Francis, it is interesting to note that she was listed as a Director and was present for every Board Meeting from her initial hiring onward. Anne received the biggest thanks of anyone in the first Annual Report dated May of 1950. War Memorial Association President Alger Shelden, Jr. remarked, “Her unfailing courtesy and cheerful spirit has covered up so many of the mistakes we have made. Mere words can’t express what the McGinty’s have done to make this Center a success and an enjoyable place to come to.”

According to the Board’s monthly records, Mrs. McGinty was indeed doing yeoman’s work from the outset. From June 1 – June 30, 1950, 12,252 people came via the19 groups that visited. Total attendance in July of 1950 was 1,485 and in August 1950, 825 as per the September figures. Returning after summer break in the autumn, September 27 – October 24, 1950, saw 3,694 people over 76 events, 31 being regular groups. November 1950 saw 96 meetings held and 3,623 attendees.

Anne behind one of her tables, undated

Dances were very popular here from the beginning and refreshments were always served. Two dances, October 9 and November 6, 1949, saw 403 youngsters. For Teen and Young Adult dances July 9, 1949 – July 31,1950, total attendance was 6,159. In December 1950, 937 “young people” attended a 9th grade open house, and the formal New Year’s Ball saw 241 couples served.

During March of 1951, there were 399 lunches, 140 dinners, and 89 teas with a total of 628 served. 34 groups and 2,594 people were in and out of the Memorial Center, an obvious illustration as to why Mrs. McGinty still had new bake ovens, large mixers, and a deep freezer at the top of her kitchen wish list.

April of 1951, there were 732 lunches served; 1,265 visitors attended teas; and 169 attended dinners.

In the President’s Report to Members dated May 7, 1951, Alger Shelden, Jr. cited an astonishing attendance of over 50,000, with food service to over 8,000 during the past year alone! Yet there were still only four fulltime employees: Mr. and Mrs. McGinty, an office manager, and the gardener. Anne had her hands full budgeting, preparing, and serving those thousands of meals.

Shelden also reported, “In the two Grosse Pointe newspapers alone, more than 430 individual articles were carried – or an average of more than four per paper per week. These were also supplemented by articles and a few spreads in the Detroit papers. Measured in column inches, the news stories in the two Grosse Pointe papers during the past year amounted to 4,121 inches; 21 pictures measured in 647 column inches were printed; and 1,861 column inches were devoted to the papers in running program listings; there were also six excellent editorials. There were over 10,000 Grosse Pointe home owners sent regular mailings from us.”

On September 1, 1952, Mr. John W. Lake was announced as the new Executive Director of the Grosse Pointe War Memorial Association, effective immediately. Mrs. McGinty reported directly to him and was made responsible for all Housekeeping and Food Service, and was “over the Houseman, the Cook, Maids, Waitresses, and other House Department personnel.” With Lake’s final approval she “could hire House Department staff and temporary help; purchase supplies; sign service contract drafts; make all food service event arrangements; set food and waitress fees; maintain records and approved vouchers for submission to the organization Treasurer; account for all food and housekeeping charges; and post Memorial Center Daily Events on the activities board.”

With that, a part time cleaner was made full time house cleaner and two women were hired part time to help Anne with event cooking. As an example, they cranked out two dozen pies and 1,000 cookies at a time for the 400-person luncheons and 300-person sit-down dinners and special events. Part time wait help was also hired as needed.

For the eight months ending March 31, 1953, Food & Catering costs were $7,656.39, a far cry from costs nowadays.

For many years, the Memorial Center shut down for several weeks to a month in the summer, usually during August. Heavy repairs, large public area projects, construction, or replacement of appliances would generally happen during this time. The McGinty’s took their vacation during this down time, as did the growing staff in subsequent years. The McGinty’s eventually purchased a cottage at Crescent Lake in Waterford Township that became their special getaway sometime in the mid- to late-1950’s. It wasn’t terribly far from Grosse Pointe, but it was far enough to allow them to forget endless maintenance projects and serving thousands of gallons of Anne’s famed “McGinty Punch” or her special English Trifle.

In 1953, John Lake offered to sleep in the House to avoid hiring overnight security while the McGinty’s went on their vacation. The couple usually went later in the summer, but wanted to go earlier that year for a very special reason: their visit home coincided with the once-in-a-lifetime coronation of Queen Elizabeth on June 2. While in England, 60-year-old Francis suffered a major heart attack. In the minutes of the July 13 meeting, the Board was very distressed to have learned of Mr. McGinty’s health emergency and made it their first topic of discussion. They wanted to make sure the McGinty’s “had the funds to finance the illness and to return home when ready.” Fortunately, Britain’s National Health Service took care of his medical expenses. By the end of August, the McGinty’s signaled they were on their way back to Grosse Pointe from Ireland, where Francis had been recovering after his release from the British hospital. (Grosse Pointe News, 8/20/1953). Like clockwork, Anne was listed in attendance at the September 14 Board Meeting.

At the October 13, 1952, meeting, Mrs. McGinty announced that over 600 people were served in one day. At the February 1953 meeting, she had reported 1,726 were served between luncheons, dinners, teas, and refreshments. By September 1953, she had served 2,058.

At the Annual Members Meeting of September 28, 1953, Lake reported over 15,000 more people had used the Memorial Center than the previous year.

As with all things, fast growth also brought some growing pains, especially for the new non-profit. There were frequent discussions about Grosse Pointe group room rentals and food prices versus non-Grosse Pointe residents – and at what percentage of Grosse Pointe membership in each club constitutes being Grosse Pointe. Similar debates were flying over the idea of weddings and veterans; what veterans’ exemptions, if any, should we accept for allowing marriages? Likewise, exactly which kinds of events are allowed and what, if anything can be sold at events? The varying food and room price quotes, and the answer as to if an event could be booked at the Memorial Center, frequently fell to Mrs. McGinty. Everyone was still feeling their way through this process with differing opinions. For example, on December 14,1953, it was decided “Detroit (and other cities’) groups using the facilities catering be required to pay room rent equivalent to that paid by Grosse Pointe groups when no food is served; the Memorial Center dinners start from $2.50 plus tax, except for service groups for whom a special meal will be prepared at $1.65. Luncheons should begin at $1.25 plus tax. Meals for weddings should start at $2.75 plus tax. Waitress fees should be $7 during the day, but $8 beginning with the dinner hour.” Debates for adjustments and refinements happened every few months as different or new situations arose. Mrs. McGinty rolled with whatever changes were instituted and adjusted her prices, menus, and plans accordingly.

During October of 1954, 3,323 were served, up from 2,852 the same month the previous year.

For Christmas time events, she’d make her “special” Christmas cookies and cakes, served with hot wassail, and McGinty Punch. The New Year’s Eve Ball was a buffet for 500 formally dressed attendees, that included cold turkey, ham, assorted relishes, breads, potato chips, cakes, hot chocolate, coffee, milk, and Punch. The 300 visitors at the New Residents’ Reception January 2, 1955, received hot wassail, coffee, assorted Christmas cookies, and cakes.

1955 was a year that signaled some possible changes ahead for Anne McGinty. With her food service in overdrive, at the July 11, 1955 meeting, it was voted that the cooks would get $12 per 150 guests, and an additional $2 for each additional 50 guests. They had previously gotten $12 for serving 300 guests. During May of 1955 alone, she served 336 luncheons for the Junior Goodwill Fair, 276 lunches for the Garden Center Fair, 300 dinners for the 1955 Graduating Class of Grosse Pointe High, and 100 breakfasts for the Y.W.C.A. Her statistics from August 31, 1954, were 26,548 meals/refreshments served as compared to August 31, 1955, at 35,941 meals/refreshments served, another large jump.

By the end of August 1955, she’d finally received her kitchen equipment: 1 Garland Hot Top range and broiler; 1 Garland burner range; 1 high shelf for open burner range; 1 fry griddle and broiler; and 1 Blodgett roaster oven, all for $1,272.25. With a new (but used) refrigerator and deep freeze installed the previous year, she was now pretty well set with professional grade kitchen appliances for serving large groups daily.

Anne & Francis stroll the knot gardens, undated

There were a few warning signs back in January that the number of bookings might not be great for the year, but that fortunately didn’t come to pass: January 1955 (2,797 served) versus January 1956 (4,733 served). Coming back after summer break was also a pleasant surprise: September 1955 (3,269 served) vs. September 1956 (4,338 served).

In the December 1955 meeting, Mrs. McGinty pleaded for the first time for more promotion surrounding her catering service as she was seeing a reduction in requests and was a bit worried about it. Unlike January’s scare, this was the first time John Lake also cautioned that there were events that were booking elsewhere that normally would have booked here, due to the groups being too large to accommodate in the House. These were the beginnings of Lake starting to think about reconfiguration or, better yet, expansion.

Another raise for the cooks was approved in November of 1956: $12 for meals of 75 people and under; $15 for every Tuesday dinner, even though less than 75 were present; and $18 for 150 or more served.

The caution lights flashed again in December of 1956 when John Lake proclaimed to the Board that bookings were down because ”there are weakness in the physical plant.” Apparently, this meant he thought some of the rooms were looking shabby, heat and lighting needed upgrading, and most importantly, there was insufficient space for larger groups. He then (perhaps oddly) proposed that the Library be turned into a small auditorium with a stage. A group was assembled to examine improving all of the facilities.

After their findings, Lake began seriously pursuing the idea of another building or extension. When William Fries’ passed a few years later in February 1959, and his very generous financial gift was made known, it was the answer to the problem of “not enough space.” But not yet knowing this, Lake started to lay the groundwork for expansion and addressed the constant parking problem back in the mid-1950’s.

The word “weddings” finally appeared during the January 1957 year wrap-up by Mrs. McGinty; there were 50 weddings, but the sizes/attendance were not noted. Wedding teas suddenly became a thing in 1958 and 1959, almost 300 of them were held.

A fulltime maintenance man started in 1959 to help Mr. McGinty, who was ready to retire. Between his old war wound, previous major heart attack, and age, it was well past time.

In the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, annual themed Gourmet events took place whereby Anne prepared dishes alongside various acclaimed chefs from famous Detroit area restaurants. For a Chinese-themed evening in February of 1961 with Mrs. Moy (of the famed Chung’s in Chinatown and Moy’s on Jefferson in the Shores), Egg Rolls, Chicken Subgum, and a surprise Chinese delicacy were created. Anne augmented the Asian theme with her own Mandarin Orange Salad and a dessert of Peach Flambe a la Russe. The room décor, floral arrangements, and service were appropriately authentic although the patrons were relieved that “chopsticks were optional.“ Her 1959 St. Patrick’s Day extravaganza was with Chef Zack from the intrepid Al Green’s (E. Jefferson, Grosse Pointe Park). It appears Chef Zack whipped up Filet de Boeuf with Marchand de Vin among other serious culinary delights. Anne, who was also of Irish extraction, accompanied his meal with her Colcannon and Soda Bread. Yet another of the Gourmet segments brought in Chef Jean Ameriguian from Little Harry’s (E. Jefferson, Detroit), who presented some of his crowd favorites with Anne. Pointers greatly looked forward to these themed Gourmet events with wonderful local chefs and Anne whipping up exotic creations in tandem.

Sometime in the late 1950’s, ads mysteriously appeared for Mrs. McGinty’s Catering. The business may have been filed under Francis’ name, but it was Anne’s outside catering business. It was located on Detroit’s west side and several of her grandchildren recall their parents helping out regularly or visiting the facility themselves when they were very young. As her relatives recalled, Anne had a lovely, warm smile and demeanor, but could be all business when needed. She was able to consistently put up the large numbers documented here and still had the drive to run a catering concern with her good name proudly attached to it.

There were 750 attendees – another great turnout - at 1960’s annual January New Residents’ Reception and “her (Anne’s) homemade goodies were enjoyed by all,” John Lake enthused.

In April 1960, the eternal battle of service and food cost percentage again raged. Mrs. McGinty and the new House Committee head tried to explain that “small meals” were “a constant loss as the same amount of help is required.” The varying costs of room rates per group or event also added to the constant explaining to understand her numbers’ reports.

Anne serves the Sr. Men’s Club (Grosse Pointe News,1/14/1962)

Comparisons for June 1959 versus June 1960: luncheons went from 635 to 766; teas went from 1,526 down to 875; dinners were up 464 to 791; refreshments went up from 1,668 to 1,987; wedding breakfasts were 200 and went down to 100; wedding teas went from 338 down to 150; desserts went from 0 up to 244; buffets also went from 0 to 385. Totals were 4,831served in June 1959 to 5,298 served in June 1960. The wedding breakfasts and wedding teas dropped off in 1960, apparently leading them to stick with just regular weddings. But there was still no alcohol allowed and limited space at that time for traditional weddings, so the other ideas were possibly workarounds tried for income.

By October 1960, attendance and catering bookings had seriously fallen off due to the limitations of the room sizes versus attendance and member count for events – the Memorial Center was seen as too small to accommodate everyone who wanted to use the facilities. Meanwhile, the legal battle trying to advance construction on William Fries’ endowment gift was being waged so they could add the larger spaces desired. The gift also had a limited time component, so Lake, the Board, and Memorial Center attorneys had serious time constraints to deal with.

In the October 1961 Board Meeting notes, the cost of the new kitchen equipment for the Fries was “not to exceed $22,188.” The new kitchen would be gas and electric as it was “too expensive to go all electric.” Anne also advised that 35% of her catering expenses were for food, 26% for help; she was 38% and 20% for December 1961.

At the first Board Meeting of the new year, January 22, 1962, Mr. Lake announced Mrs. McGinty’s retirement effective as of March 1, 1962. The Board regretfully accepted the news and started looking for her replacement immediately. At the next Board Meeting, February 19,1962, Miss Helen Blair of Nashville, Tennessee was introduced as Mrs. McGinty’s successor.

March 5, 1962, was scheduled as Anne’s retirement party, 7pm and $2.50 per plate for attendees. Organizations who had dealt with Anne were also invited to attend, hence the charge; Helen Blair prepared the dinner. The McGinty’s announced that their immediate plan was to follow the American Curling Team to Scotland, London, and Ireland for competitions, as Francis was a rabid curling fan. The $300 Anne was given as a retirement gift from the Board helped their plans. They’d then return home from the UK to Crescent Lake and some well-deserved quiet.

The House apartment was redecorated after the McGinty’s departure. At the May meeting, the Board decided to rent their former living room and one bedroom for $500 a year. Not long thereafter, John Lake moved into the remainder of the apartment, where he resided for many years.

The Fries Auditorium grand opening date had been pushed back a few times due to construction and other issues and was now scheduled for November 30, 1962. The grand opening was to be a black tie affair featuring a Spanish ballet group and seating for 450; the first 300 guests would be served in the new Crystal Ballroom, with the remainder in the House. December 2 was the actual dedication festivities for the general public to attend.

As late as November 19, Helen Blair was still submitting emergency kitchen needs lists to be approved by the Board in order to serve for the formal opening 11 days away. Reportedly, the Board were very happy with Miss Blair and she and her staff were able to pull off the two Fries’ openings without incident.

On December 16, 1962, Mrs. Marion Alger died at her winter home in Boca Grande, Florida after just attending the Fries’ grand opening. Marion was involved with 32 Lakeshore Road beginning in 1907, when she and Russell first decided to call in Charles Platt to design and build their dream house there; through Russell’s death and the DIA years; her gifting the estate to the War Memorial Association and serving on its Board; and her final work advising on the Fries Auditorium plans and witnessing its opening 55 years later. The true end of an era.

Carefree, retired McGinty’s, late 1970’s

The McGinty’s lived at their cottage in Crescent Lake for quite a time. Later, they took a little condominium around 12 Mile and Woodward in Royal Oak until Francis McGinty passed at 87 years old on October 29, 1980. His service was held at the nearby National Shrine of the Little Flower Basilica before he was interred at Assumption Grotto Cemetery on Gratiot Avenue off of Mapleridge on Detroit’s east side. Sometime after Francis passed, Anne McGinty moved from their condo to The Whittier off Jefferson Avenue in Indian Village, which served as senior citizen housing at the time. She passed June 5, 1989, at 92 years and joined Francis at Assumption Grotto Cemetery.

If you’re ever in the Alger House early in the morning and catch a whiff of something wonderful wafting out of the old kitchen, you might almost wonder if Anne is back behind the big stove, happily whipping up one of her wonderful meals or a big batch of her “special” cookies.

Credits & citations: Jack Oliver’s Pointer of Interest, Grosse Pointe News (3/20/1958); interviews with the McGinty’s grandchildren; and TWM Board Meeting records

Photo credits: All photos courtesy of the McGinty’s, except as noted.

Writer’s note: None of Anne McGinty’s recipes could be found before the print deadline. If any are located in the future, they will be reprinted by TWM.

The Lost Men of World War II

This past Saturday was the 83rd anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor signaling the United States’ official entry into World War II. In memoriam, we look at the final days of some of the MIAs from that war who have finally been recovered from the Pacific and European Theaters.

This past Saturday was the 83rd anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor signaling the United States’ official entry into World War II. In memoriam, we look at the final days of some of the MIAs from that war who have finally been recovered from the Pacific and European Theaters.

The first story is about the lost crew of the B-24H Liberator, the Little Joe (#42-521850).

The ill-fated crew of the Little Joe.

The U.S. Army Air Forces crew of ten were assigned to the 732nd Bombardment Squadron, 453rd Bombardment Group, 2nd Combat Bomb Wing, 2nd Air Division, 8th Air Force. They had taken off April 8, 1944, from Royal Air Force Station Old Buckenham, England on a bombing mission seeking enemy targets in Brunswick, Germany. Somewhere over the Salzwedel, Germany area, the Little Joe suddenly went missing from formation. The other planes didn’t see a hit, crash, or bail out; it just disappeared.

The region between Salzwedel and Wistedt was riddled with downed bombers, but the Little Joe didn’t appear on the AGRU (American Graves Registration Unit) KU (Germany's aircraft combat records) detailing a crash or burials. None of the crewmembers were recovered during or shortly after the war, so all ten were officially listed as Unaccounted For for several decades - until very recently.

In 2015, MAACRT (Missing Allied Aircrew Research Team), an independent research group, contacted the DPAA (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency) with information remembered by local elders living near Wistedt, Germany regarding two old crash sites. Only one site was located post-War, but the DPAA investigators found wreckage and osseous remains at the second site off the new tip. At the time no matches could be made to Unknowns.

In 2021 and 2023, DPAA investigators returned to the second site for additional excavation for equipment and any osseous remains; the results were again sent to their laboratory. This time, using DPAA scientists’ anthropological and dental analysis, and the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System’s mtDNA and Y-STR analysis, some positive identifications were made.

SSG Ralph Mourer and wife

Hailing from Colorado, Staff Sargeant Ralph Lavon Mourer was the 23-year-old radio operator aboard the Little Joe. On June 20, 2024, his status was officially changed to Accounted For. A rosette indicating this change was placed on Mourer’s name inscribed on the Walls of the Missing at Netherlands American Cemetery and Memorial, Margraten, Netherlands.

Walls of the Missing, Netherlands American Cemetery and Memorial, Margraten, Netherlands

Mourer’s parents, siblings, and wife were all long deceased with burial sites in various States. His only child, Victor Lavon Mourer, whom his wife was carrying when SSG Mourer was killed, was also long gone, buried at Adrian, Michigan’s Oakwood Cemetery. In the spring of 2025, SSG Ralph L. Mourer will likewise be buried in Adrian near the son he never got to see.

22-year-old 2nd Lieutenant Francis E. Callahan of New York was the navigator of the Little Joe. His remains were also identified by the DPAA through dental and anthropological evidence from the second crash site. Once he was Accounted For June 20, 2024, a rosette was added next to his name on the Walls of the Missing in Margraten. A 2025 burial at Arlington National Cemetery is planned per a New York newspaper report (Livingston County News, 8/13/24). As with most of his crewmates, Callahan’s immediate family is deceased.

Sargeant Henry Hanes Allen, Jr., 20, of Georgia was the Little Joe’s top turret gunner. His identification was released June 20, 2024, and his status changed to Accounted For; a rosette was added next to his name in Margraten. Allen’s mother swore until the day she died in 2003 that “he might walk through that door.” Eighty years later, his cousins finally laid Henry to rest October 12, 2024, back home in Covington, GA.

Staff Sargeant Hubert Yeary, 20, of Virginia was the baby-faced ball tail gunner of the bomber. Herbert and his twin brother, Herbert, enlisted together in January 1943. Yeary was positively identified June 20, 2024, and a rosette added next to his name in Margraten showing he was Accounted For. With his parents and four siblings, including Herbert (d. 1998) all long deceased, no burial time or location has yet been announced. Once the plans are known, the DPAA will release the information to the public.

Twins Hubert and Herbert enlisting

Little Joe’s left waist gunner was Technical Sargeant Sanford Gordon Roy, 31, from Tennessee. Roy was quite a bit older than the rest of his crew and was also an aviation mechanic. His remains were Accounted For June 24, 2024, and a rosette added to his name on the Walls of the Missing. There was already a memorial cenotaph at Chattanooga’s Greenwood Cemetery, but T/Sgt Roy’s actual funeral with full military honors will take place at Greenwood on the 81st anniversary of his death, April 8, 2025 (Chattanooga Times Free Press, 11/27/2024). His great nephews, great nieces, and great- great niece will be in attendance to welcome him home.

T/Sgt Sanford Roy and crewmates atop the newly painted Little Joe

The pilot of the Little Joe was 1st Lieutenant Joe Allen DeJarnette of Kentucky. On April 8, 1944, he was last witnessed piloting the bomber “at 1405 hours near Salzwedel.” He was likewise Accounted For June 24, 2024, and a rosette added next to his name in Margraten. Joe’s parents, two sisters, and naval ensign brother are all deceased. There are no burial plans at this time, but hopefully he can be returned by a distant relative to his family resting place at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Erlanger, KY.

Little Joe’s co-pilot was 2nd Lieutenant Robert D. McKee, hailing from Oregon. McKee was Accounted For June 24, 1944, and a rosette affixed next to his name in Margraten. His mother and two siblings are deceased; there is no burial information for 2LT McKee at this time.

The bombardier aboard the Little Joe was 2nd Lieutenant John Harvey Harris, a happy 23-year-old from North Carolina. Harris was Accounted For June 20, 2024, and a rosette was added next to his name in Margraten. Although he came from a large family, his parents and seven siblings are also deceased. 2LT Harris’ nephew was there to welcome him recently to Fort Jackson National Cemetery in Columbia, SC, where he received a funeral with full military honors on November 19, 2024.

The cases for the two still Unaccounted For members of the Little Joe are now listed as Active Pursuit: Staff Sargeant Sidney A. Johnson, 23, the right waist gunner from California and Sargeant Frank J. Vincze, 29, the tail gunner from Pennsylvania. With the DPAA’s success in finding and identifying the original eight men of the crew, we can only hope that they can soon do the same for these two brave airmen and return them home.

***

U.S. Army Private First Class Gordon N. Larson, 22, of Washington was a member of Battery B, 59th Coast Artillery Regiment. U.S. Army Private James S. Mitchell, 25, of California, was of Company B, 31st Infantry Regiment, and also stationed on the Bataan peninsula. On April 9, 1942, Larson and Mitchell were among those reported captured when U.S. forces in Bataan surrendered to the Japanese. They were subjected to the infamous 65-mile Bataan Death March and then held at the Cabanatuan POW Camp #1. More than 2,500 POWs perished in this camp during the War. According to prison camp and other historical records, Larson died Nov. 14, 1942, and was buried along with other deceased prisoners in the local Cabanatuan Camp Cemetery in Common Grave 723. Mitchell followed on Jan. 7, 1943, and was buried in Cabanatuan Camp Cemetery in Common Grave 816.

Following the war, American Graves Registration Service (AGRS) personnel exhumed those buried at the Cabanatuan Cemetery and relocated the remains to a temporary U.S. military mausoleum near Manila. In 1947, the AGRS examined the remains in an attempt to identify them. Of the sets of remains from the Common Graves, neither were identified. The unidentified remains were then buried at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial (MACM) as Unknowns.

In 2018, as part of the Cabanatuan Project, the DPAA exhumed the remains associated with Common Graves 723 and 816 and sent them to the DPAA laboratory for analysis.

To identify Larson’s (8/12/2024) and Mitchell’s (9/30/2024) remains, scientists from the DPAA used dental and anthropological analysis, as well as circumstantial evidence. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) analysis.

Although interred as Unknowns in MACM, Larson’s and Mitchell’s graves were meticulously cared for over the past 70 years by the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC). Today, both men are memorialized on the Walls of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in the Philippines. Rosettes will be placed next to their names to indicate they have been Accounted For.

PFC Gordon Larson’s and PV2 James Mitchell’s funeral locations and dates have yet to be determined.

***

U.S. Army Air Forces Staff Sargeant Yuen Hop, 20, of Sebastopol, California, was assigned to the 368th Bombardment Squadron, 306th Bombardment Group, 1st Bombardment Division, 8th Air Force, in the European Theater. On December 29, 1944, Hop was a waist gunner on a B-17G Flying Fortress when his plane was hit over Bingen, Germany and the crew were forced to bail. One died at the scene, and five were captured and became POWs but survived the War. Hop, and two other crewmen, were Unaccounted For.

AGRC continued to hunt for the three missing crew members 1946 – 1950, but finally ceased after their investigations were deemed complete; the three were then officially listed as Non-recoverable.

In 2013, DPAA researchers working with local Germans recovered documents from the state archive at Koblenz, which appeared to contain information on the loss of three captured airmen. These documents referenced War Crimes case #12-1254, which indicated Hop was captured and killed by German SS troops near the town of Kamp-Bornhofen and buried in the local cemetery there. This was the first time the three had been referred to as German POWs.

Between May 2021 and August 2022, DPAA teams excavated a suspected burial site in the Kamp-Bornhofen Cemetery, where the three airmen were believed to be buried. Under the supervision and direction of two Scientific Recovery Experts, the team recovered possible osseous remains and associated materials. These items were transferred to the DPAA Laboratory for analysis and identification.

To identify Hop’s remains (6/18/2024), scientists from the DPAA used anthropological analysis. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and autosomal DNA (auSTR) analysis.

Hop’s name is recorded on the Walls of the Missing at Lorraine American Cemetery, St. Avold, France. A rosette was placed next to his name to indicate he had been Accounted For. A memorial cenotaph bears his name at San Francisco National Cemetery.

SSG Yuen Hop’s funeral location and date have yet to be determined.

***

Massachusetts local star athletes and best friends, U.S. Army Air Forces Private 1st Class Bernard J. Calvi, 23, and U.S. Army Air Forces Corporal William Edward Gilman, 24, enlisted together September 14, 1940. Both men were assigned to the 17th Pursuit Squadron, 24th Pursuit Group, and stationed near Manila.

BFFs Bernard Calvi and William Gilman enlisting

On April 9, 1942, they were among those captured when U.S. forces surrendered to the Japanese. They too were subjected to the Bataan Death March and then held at POW Camp 1 at Cabanatuan. PV2 Calvi was the first to die, on July 16, 1942. CPL Gilman followed his buddy 40 days later, on August 25; both died of dysentery and malnutrition. Calvi was buried in Common Grave 316, but Gilman’s actual grave site was unknown; his status is currently listed as Active Pursuit.

PV2 Calvi was Accounted For September 16, 2024, by the DPAA and a rosette placed next to his name on the Walls of the Missing. His remains were sent from the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial, Philippines to North Adams, Massachusetts. His funeral service with full military honors takes place at noon today, December 10, 2024, at St. Elizabeth of Hungary Catholic Church, 84 years after Bernard and his best friend, Bill Gilman, left town to go serve their country together and, ultimately, die together.

***

After the DPAA positively identifies remains, they remand custody to the respective branch of service. In the instances above, because the U.S. Air Forces was then a branch of the U.S. Army, the U.S. Army’s Past Conflicts Repatriation Branch (PCRB) and U.S. Army Human Resources Command were tasked with repatriating the recovered personnel. Each branch of the military has a similar mortuary office and protocol for handling newly Accounted For service members.

An enormous amount of research is undertaken to locate their surviving family members. In the case of World War II and Korean War personnel, oft times the immediate family is also deceased, and distant kin is searched for. An important line at the bottom of each DPAA recovery announcement reads: If you are a family member of this service member, DPAA can provide you with additional information and analysis of your case. Please contact your casualty office representative.

In the event that no one comes forward to claim their recovered kin, the appropriate mortuary affairs branch then has the authority to inter the personnel in the closest national (military) cemetery to their last known home address.

Whether it is a relative that is finally sent their loved one for burial in their family plot, or the U.S. military installing them in a national cemetery with full honors, our fallen are treated with the greatest respect and dignity that can be afforded for their ultimate sacrifice.

CREDITS: Thank you to Marty Eddy, Michigan Coordinator, National League of POW/MIA Families

Alger Service Through the Ages

In this special Veterans Day edition of History Corner, we look at the long line of Alger family members who have served in the military, dating back to the Battle of Hastings.

The Alger’s have a very long history of patriotic and military service going back to when there were not many official written records documenting such things.

General Russell A. Alger’s parents, Russell Alger and Catherine Moulton of rural Lafayette Township, Medina County, Ohio, trace their ancestry back to Sir Thomas de Moulton, a knight who fought with King William I, better known as William the Conqueror, at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. If one must fight, one might as well fight with “one of the greatest soldiers and rulers of the Middle Ages” (Brittanica). Finding himself in great favor with the King for his battlefield efforts, Sir Thomas was rewarded with a large swath of land which officially became Moulton, Lincolnshire, England around 1100.

Centuries later, Gen. Alger’s maternal great-great-great-great-grandfather arrived in the United States. Master shipbuilder Robert Moulton relocated from Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, England to Salem, Massachusetts in 1629, along with his adult son, Robert Jr., a Church of England clergyman. Robert Sr. was loosely anointed “in charge” by the governor and was a very well respected community leader with extensive real estate holdings in the Charlestown area of Boston. The site of his former home became known as Moulton Point and was where the British landed when they crossed from Boston to engage in the Battle of Bunker Hill; both father and son died in 1655. Robert Moulton, III also lived in Salem, when it was popular to fight each other during the witch trials, which he reportedly engaged in.

Jumping ahead to the 5th generation of Robert Moulton descendants, one finds Captain Freeborn Moulton (4/3/1717 – 6/9/1792), the great-great-grandfather of Gen. Russell A. Alger (a 7th generation descendent). Capt. Moulton was born in Windham, CT and is Gen. Alger’s direct tie-in to the Revolutionary War. As part of Colonel Danielson’s Regiment, Freeman was Captain of the Monson minutemen and led the march to Cambridge in response to the Lexington Alarm issued April 19, 1775, kicking off the Revolutionary War. His memorial cenotaph is at Moulton Hill Cemetery, Monson, Hampden County, MA.

Cenotaph for Capt. Freeborn Moulton at Moulton Hill Cemetery in Monson, MA.

His son, also named Freeborn (4/9/1746 – 1815), is likewise listed as being a Revolutionary War veteran from Monson in the Moulton Annul but I’ve not been able to independently 100% confirm this. However, the junior Freeman’s age is more in line with engaging in serious battle.

Although there is much less information immediately available on the paternal side of the Alger family lineage, there are several historical references to “a great grandfather” fighting in the Revolutionary War. Neither the DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution) nor I have found such evidence, but there may have been an ancestor, potentially Capt. John Alger, Jr., in the earlier and much lesser documented French and Indian War (1755 – 1762). The Alger’s, via Jonathon Alger, came from England around 1630 and landed in Connecticut living primarily in the Old Lyme area. If Capt. John was indeed a war veteran, he was the only one that descended from Jonathon until General Alger.

Revolutionary War Colonel Eli Brownson (5/31/1748 - 3/28/1830) was related to Annette Henry Alger, Gen. Alger’s wife. Born in Salisbury, Litchfield, Connecticut, he registered for the military in 1777 and eventually died in Sunderland, Bennington, Vermont. Annette had him listed as her official Patriot in the DAR’s records, so he is 100% confirmed.

By now the story of General Russell Alexander Alger’s military service should be fairly well known. He signed up to join the Union Army within two weeks of his marriage to Annette as Ft. Sumter had been fired upon and he felt it was his patriotic duty. He mustered into the Civil War as Captain of Company C, 2nd Michigan Cavalry. Rising quickly through the ranks, he then became Lieutenant Colonel of the Michigan 6th Cavalry, then Colonel of the Michigan 5th Cavalry, General Custer’s famous brigade. He was severely injured twice: at the Battle of Booneville (MS, 7/2/1862), where he was also taken prisoner but escaped within 24 hours, then injured again at the Battle of Boonesboro (MD, 7/6/1864). Throughout the winter of 1863 – 1864 he was on special assignment visiting all of the U.S. field armies and camps on the orders of President Lincoln and reported only to him. Due to health issues from his war injuries, he retired from the military autumn of 1864. As with many veterans today, he continued to have service-related health issues throughout his lifetime. In total, he had fought in 66 battles and skirmishes, several of them the fiercest of the Civil War. Alger was considered a brilliant military strategist by Generals’ Custer, Sheridan, McClellan, and Kilpatrick. He was breveted as Brigadier General and Major General for “gallant and meritorious services on the field.”

Gen. Alger went on to bring an important change for veterans by vastly improving their pensions. As governor, he opened the Michigan Soldiers’ Home (now the Michigan Veterans’ Facility) in 1886 in Grand Rapids. He became the national Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) 1889 – 1890 and was a member of the Massachusetts Commandry of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS) before becoming a founding member of the Michigan Commandry. Both fraternal organizations were open only to Civil War veterans in good standing and had huge memberships. The Michigan Commandry was the driving force behind the 1921 installation of the impressive Russell Alger Memorial Fountain located in Grand Circus Park honoring the General.

Russell A. Alger Memorial Fountain at Grand Circus Park in Detroit.

Alger went on to be vigorously promoted twice as a Republican candidate for U.S. president, became a Michigan state governor, the U.S. Secretary of War, and a two-time Michigan Senator before dying in office in early 1907.

Funeral arrangements were handled by longtime friend, Truman Newberry (then Asst. Secretary of the Navy) and the GAR at Annette’s request. Although he had requested a simple funeral in keeping with his modest nature, he received two remarkable funerals: a political VIP-filled one in Washington, D.C. where he died and a massive one attended by thousands in Detroit on a frigid January day, the latter being essentially a state funeral.

In addition to his active pallbearers, Alger had some 86 honorary pallbearers, consisting of some of the biggest names in Michigan history: Hudson, Buhl, Joy, Newberry, McMillan, Ferry, et al. He also had a very lengthy funeral cortege consisting of the joint committee of the national House and Senate; state and national VIPs; three full bands; forty mounted police; the Corinthians’ and other Michigan Freemason groups’ members; 15 different military organizations’ and camps’ members (GAR, Loyal Legion, et al.); state, federal, and county officials; and the Newsboys’ Association with hundreds of men and boys bringing up the rear before the general public joined the solemn march. The public viewing was only for four hours exactly, but 20,000 people crammed into City Hall to file past his casket. They followed the General from City Hall down Fort St. to Jefferson Ave., then marched to Elmwood Cemetery and the Alger mausoleum. Russell Alger, the battered Civil War veteran, even received flowers from a group of top former Confederate officers in a stunning show of respect. Gen. Alger dedicated his book The Spanish-American War to “the American Soldier and Sailor.” Although he came from impoverished and very difficult beginnings to achieve enormous fame and fortune, the unassuming Alger most likely still thought of himself as a simple American patriot, soldier, and businessman.